3D Bioprinting - The Future of Transplants

Imagine a world where damaged organs can be replaced with brand-new, customized ones, where skin grafts are printed on demand for burn victims, and where drug testing no longer relies on animal models. Every year, thousands of patients around the world wait for life-saving organ transplants, but the shortage of donors means many never get the chance. Even for those who do, the risk of rejection and lifelong immunosuppressive treatments remains a major challenge. But what if we could bioprint fully functional human organs made from a patient’s own cells?

3D bioprinting is turning this once-unthinkable idea into reality. It combines biotechnology and medical engineering to print tissue layers that ultimately mimic human organs. While we are not yet at the stage of transplantable printed hearts, recent breakthroughs suggest that the era of lab-grown organs is closer than ever. Could bioprinting be the future of transplants?

The History of 3D Bioprinting – where it all began

3D bioprinting has evolved rapidly as researchers continue to drive innovation in this field. The foundation for this technology dates back to the 1980s, when 3D printing was first invented. In 1983, Dr Charles Hull invented Stereolithography - a method originally designed for creating plastic prototypes. While its initial purpose was unrelated to bioprinting, it paved the way for applying similar principles to biological structures.

The first major step toward bioprinting occurred in 1988 when Robert J Klebe pioneered the use of an inkjet printer to deposit living cells—a breakthrough that demonstrated the potential of printing functional biological tissues.

As bioprinting has advanced beyond its initial stages, new methods and techniques have been discovered. With so much potential to create life-changing solutions, this revolutionary technology has gained widespread interest among scientists, yet we are only beginning to uncover its full capabilities…

What is 3D Bioprinting and how does it work?

Can you believe that a meniscus can be produced in 30 minutes? At the heart of bioprinting is a special material known as bioink. It is not just ordinary ink, but a mixture of living cells, nutrients, and matrices that provide structural support; like a master painter blending colours on a palette, scientists can create any array of bioinks to produce intricate designs of life.

The bioinks can be made from a variety of synthetic or natural materials. One example is alginate, a natural polysaccharide derived from brown algae. It forms hydrogels with properties similar to the extracellular matrix, making it a promising biopolymer for applications such as cartilage repair, wound healing, and drug delivery. In contrast, gelatin, a denatured form of collagen, is valued for its thermoresponsive properties and ability to promote cell adhesion. It is synthetically modified for use in bone tissue, liver tissue, and skin regeneration. The final example is dECM—decellularized extracellular matrix—a biomaterial from natural tissues where cells are removed, leaving a scaffold that retains the tissue’s original structure and composition.

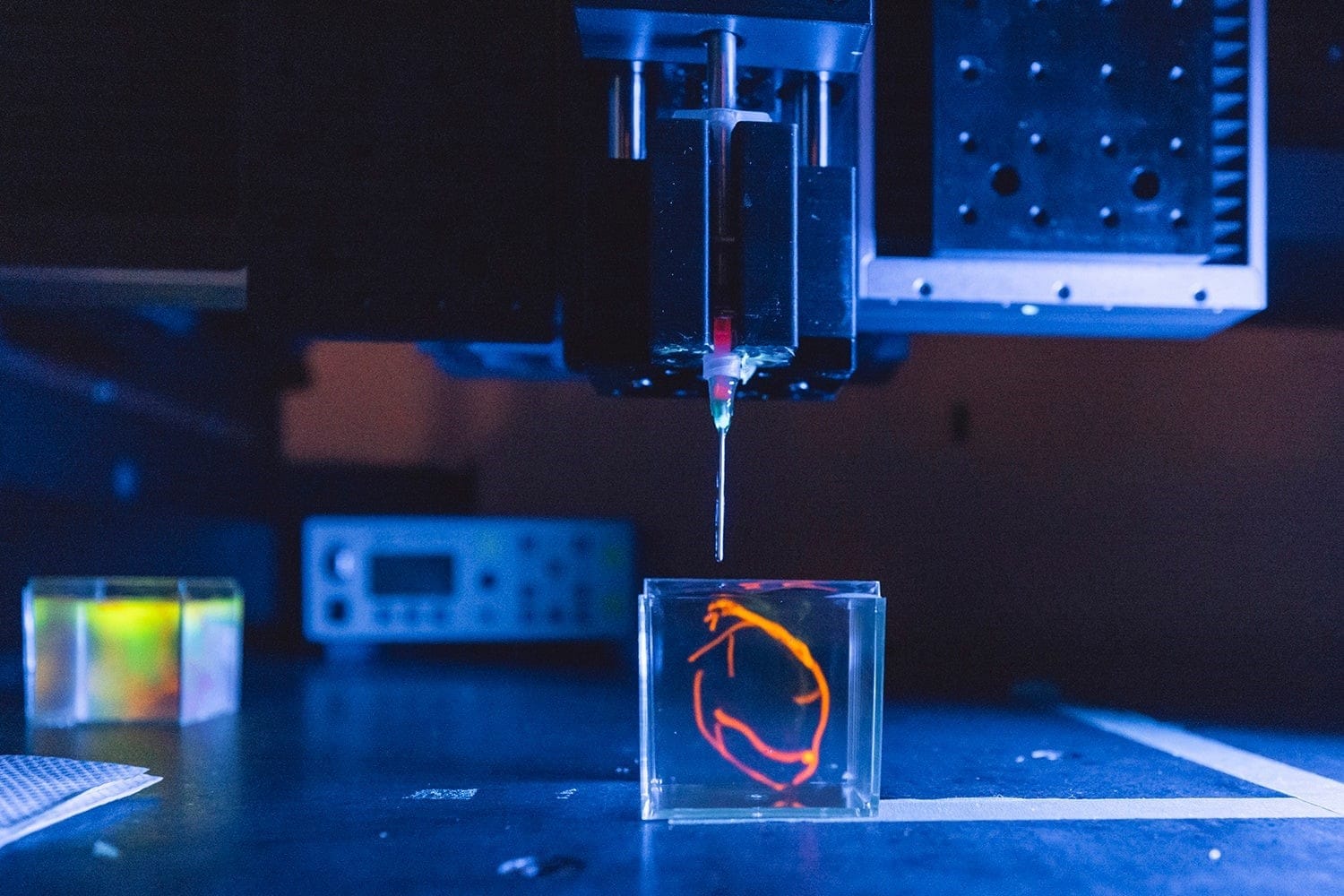

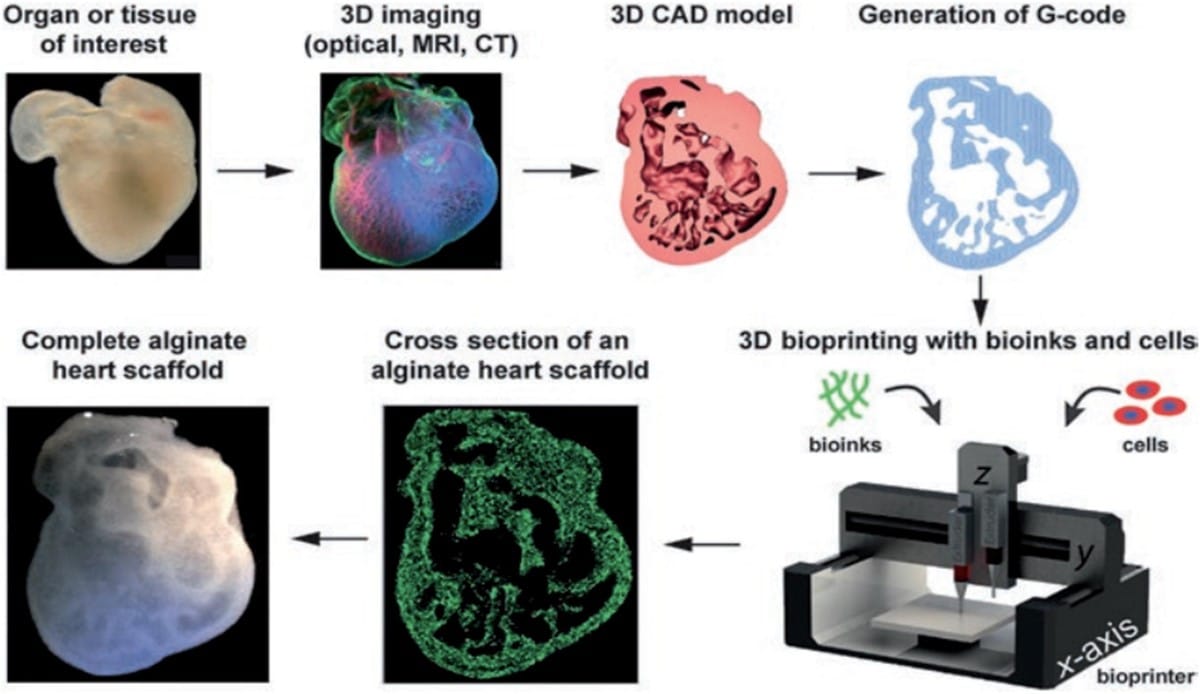

3D bioprinting is a manufacturing process that use bioinks to print living cells and tissues, building structures layer by layer to mimic the composition and behaviour of natural tissues. The process starts with a digital model generated from MRI or CT scans, guiding the printer to deposit layers of cells to form tissues – either on a surface or in a liquid bath. After printing, some bioinks will stiffen immediately, and others need UV light or an additional chemical or physical process to stabilize the structure. The constructs are then put into incubators for them to mature before implanting or testing. If the printing process is successful, the cells in the synthetic tissue will begin to behave the same way cells do in real tissues! They signal to each other, exchange nutrients, and divide.

3D bioprinters are specialised to handle bioinks containing living cells without excessive damage. The compatibility of the printer and bioink is crucial, as each printer type affects cell viability, density, and resolution. The four main bioprinting technologies are inkjet-based, extrusion-based, laser-assisted, and stereolithography-based. We will be focusing on the first three techniques, where extrusion-based bioprinting is the most widely used in the scientific field.

Inkjet Bioprinting

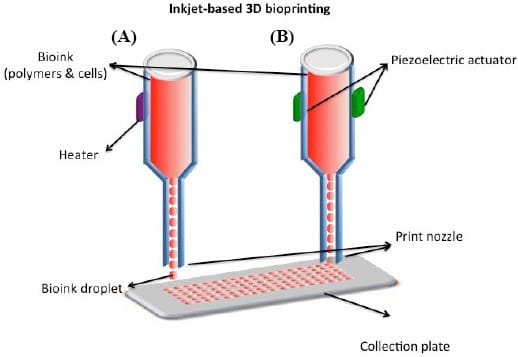

This is one of the most well known printing methods. Inkjet bioprinters use thermal or physical compression to generate and shoot off droplets. Without direct contact, image reconstructions are based on the precise positioning of bioink droplets of picolitre volume (1-100 pl) onto the medium (*A picolitre (pL) is one trillionth of a litre, it is so small that it's not visible to the human eye, i.e. a raindrop can contain thousands of picolitres).

This method can be divided into two main types: continuous inkjet (CIJ) printing and drop-on-demand (DOD) printing. CIJ printing produces a steady stream of bioink droplets based on the tendency of liquid flow and conformational changes. With the help of an electric or magnetic field, droplets become electrified and can get to their own position. In contrast, DOD printers only release droplets on a substrate when required. While CIJ printing is faster, it requires conductible bioinks and contains high contamination risks. Therefore DOD is much preferred for biomaterial sedimentation and composition due to its accuracy and minimal bioink waste.

Inkjet printers are known for their high printing speed and precise droplet control. However, its functions are limited by the need for low-viscosity bioinks, restricting structural integrity of printed products. As a result, while inkjet-based bioprinting is useful for certain applications, it is still in its early stages for large-scale organ printing, with extrusion-based bioprinting being more widely used for complex tissue engineering, which we are coming to next!

Extrusion-based bioprinting

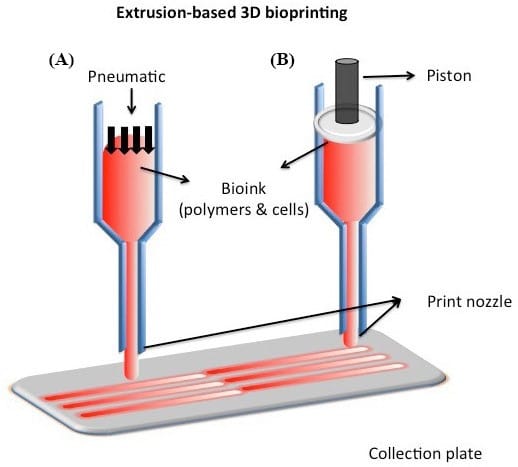

Unlike thermal inkjet bioprinters which can only process low-viscosity bioinks, extrusion bioprinting can accommodate a much wider range of viscosities by using a disposable medical plastic syringe to dispense bioinks onto sterile biomaterials, hence why it is the most widely used method. Three different systems are used to control the flow of bioinks - pneumatic, piston-driven, and screw-driven systems. Pneumatic system uses air pressure to push bioink through a nozzle for controlled deposition; Piston-driven system uses a mechanical piston to force bioink out of the nozzle, providing accurate volume control but potentially limiting the types of bioinks that can be extruded; Screw-driven system uses a rotating screw to move bioink forward, making it particularly effective for handling viscous bioinks that gives continuous and consistent extrusion. In this system, bioinks are deposited into cylindrical filaments, which are then interconnected using ultraviolet light, enzymes, or biochemical agents to form functional tissue structures. Precise control of temperature, air pressure, and extrusion speed is very important in maintaining the viscosity and preserving cell viability.

Extrusion-based bioprinters typically use a three-axis automated system controlled by computer-aided design (CAD) models, enabling the production of large scale structures that mimic both micro and macro-physiological environments. It is currently the only technology capable of this. The method has been successfully used to bioprint various biopolymers, including DNA, RNA, and peptide fibres, and is widely regarded as a reliable approach for fabricating tissue scaffolds and implantable prostheses. With the ability to manufacture complex tissues and organs, extrusion-based bioprinting is paving the way for advanced tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

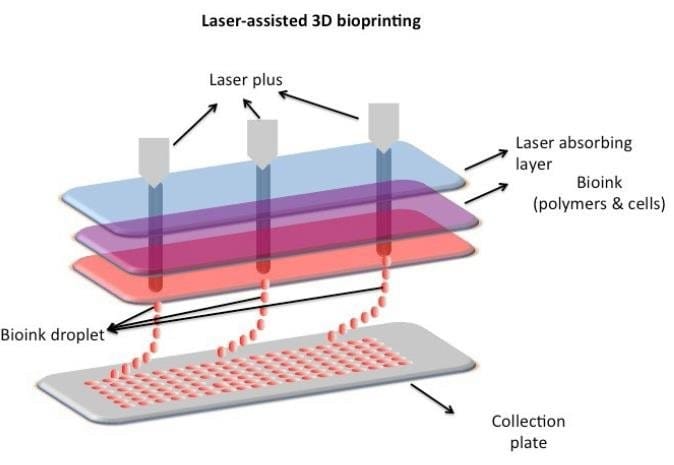

Laser-assisted 3D bioprinting

While extrusion-based bioprinting is widely used, laser-assisted bioprinting offers even greater precision, though it comes with challenges. Laser-assisted bioprinting (LAB) uses laser pulses to generate high-pressure bubbles, propelling bioink droplets from a donor substrate onto a receiving surface. A typical LAB system consists of an infrared pulsed laser, a donor substrate coated with a thin metallic layer such as gold or titanium, and a receiving substrate. When the laser vaporizes the metal film, bioink droplets are ejected and deposited onto the targeted surface. LAB are capable in creating high cell densities (~10⁸ cells/mL) and precise spatial accuracy (>5 μm), making it a perfect tool for complex tissue fabrication. However, challenges such as limited material compatibility, gravitational settling (where bioinks separate if not properly stabilized, leading to uneven cell distribution), and long processing times remain barriers to widespread adoption. Additionally, the high cost of laser-assisted bioprinters limits their accessibility for large-scale organ 3D bioprinting.

Advances in 3D Bioprinting

3D bioprinting has transformed multiple fields, making significant contributions to medical research and regenerative medicine. Bioprinted structures provide a more biologically relevant platform for studying human physiology, surpassing the limitations of traditional 2D cell cultures. For example, researchers are becoming less reliant on animal models by utilizing 3D-printed human tissues, this offers more precisive and ethical alternatives for studying drug effects and disease toxicity and progression. Cancer research is currently a major focus in the scientific field, and traditional 2D tumour models has significant limitations in replicating the complex physiological environment necessary for studying cancer pathogenesis and metastasis. Their inability to capture interactions with neighbouring cells and substrates hugely limits their clinical relevance in research. With inkjet-based bioprinting, we have fabricated models of human ovarian cancer (OVCAR-5) alongside MRC-5 fibroblasts, which allows much more precise studies of tumour behaviour.

We can already 3D print relatively simple structures such as tissues, skin, and cartilage, with printed tissue successfully promoting facial nerve regeneration in rats. The most fascinating part is that researchers have created miniature, semi-functional versions of kidneys, livers, and hearts!

Near the year 2000, the field of tissue engineering began to gain attention. A major breakthrough occurred in 2006, where researchers led by Dr Anthony Atala successfully implanted lab-grown bladders into patients with spina bifida. The bladders were created by seeding patient-derived urothelial and smooth muscle cells onto a biodegrable of collagen and polyglycolic acid. They are matured in a bioreactor before implantation. Although the implanted bladders functioned in patients and reduced complications associated with traditional bladder surgery, incomplete muscle regeneration and vascularization of organs causes cells to die overtime, that’s why fully bioprinted bladders are still in the research phase, with ongoing efforts to develop functional models that are suitable for clinical use.

Hearts

The heart is one of the most vital and complex organs in the human body, playing a crucial role in maintaining life by pumping nutrients and oxygenated blood throughout the circulatory system. However, cardiovascular disease is one of the leading causes of death worldwide, accounting for approximately 15% of all deaths. For patients suffering from end-stage heart failure, heart transplantation is often the only available treatment.

In recent years, scientists have made remarkable progress toward bioprinting hearts. 3D-printed organs have been making the headlines for a couple of years now. In 2013, a company called Organovo produced the first prototype of a human liver using 3D bioprinting; In a major medical breakthrough in 2019, researchers at Tel Aviv University printed the world’s first vascularized, engineered 3D heart using a patient’s own cells and biological materials. Though too small for transplantation, it successfully replicated muscle, blood vessels, and heart chambers, demonstrating the potential of bioprinting a fully functional heart.

The secret to a new heart

For research, a biopsy of fatty tissue is taken from patients. The cellular and acellular materials of the tissue are then separated. While the cells are reprogrammed to become pluripotent stem cells, the extracellular matrix (ECM), a three-dimensional network of extracellular macromolecules such as collagen and glycoproteins, are processed into a personalised hydrogel that serves as the printing "ink".

After being mixed with the hydrogel, the cells are efficiently differentiated to cardiac or endothelial cells to create patient-specific, immune-compatible cardiac patches with blood vessels and, subsequently, an entire heart. The use of the patient’s own cells is crucial to successfully engineer tissues and organs.

Some more?...

In 2022, scientists at Harvard and the Wyss Institute created cardiac tissue from stem cells that can contract and beat like a real heart, allowing patches for repairing damaged heart tissue before full transplants are feasible... They used multiple methods of 3D-printing living biological tissues with built-in vascular channels that ensures the delivery of critical nutrients to cells throughout a tissue. One of the approaches prints a vascular network of endothelial cells within a silicone mould, followed by stem cells and an extracellular matrix to form a functional soft tissue structure. These tissues can be immediately perfused with nutrients to support cell survival and maturation.

The SWIFT method was then developed in order to achieve high cell density. It concentrates stem cells into a dense living matrix to 3D print a gel based vascular network, which is later removed to create embedded blood vessels. When applied to heart cells, they begin spontaneously beating, mimicking the natural heart tissue. An enhanced version of it called co-SWIFT further improves the biomimicry of the tissues by integrating endothelial cells into the printed vascular structure.

One of Wydd Institute’s 2024-2025 Validation Projects is the RAPID-Vasc project, it is on the way of pioneering a method to rapidly generate high-cell-density engineered vasculature within hydrogels. This research focuses on developing hollow channel networks that enhance blood flow in both laboratory and clinical applications.

The Future of Bioprinting Organs

The future scenario of 3D bioprinting is that no more organ donors are needed, as personalized human organs can be printed using the patients’ own cells or stem cells as a base. For adults, the donor organs can last 20-30 years after transplantation, which means it is almost as good as a cure if you are around 60-70 years old. However, for a child, let’s say at the age of 5, needing a transplant, knowing that after 20-30 years the transplant may be rejected by a sudden immune reaction, it is clearly not the ideal situation to be in. Therefore it is important for us to be able to print crucial living pieces of the heart, such as valves and ventricles that can grow with the patient as well.

Challenges faced by Researchers

Replicating the complex biochemical environment of a major organ is a steep challenge. From the concept of bioprinter usage, the most popular extrusion-based bioprinting may destroy a significant percentage of cells in the ink if the nozzle is too small, or if the printing pressure is too high. One of the most formidable challenges is how to supply sufficient oxygen and nutrients to all the cells in a full-sized organ. As tissues get thicker, the cells in their interior are no longer in direct contact with the growing medium in the lab, which causes them to die. This is why the greatest successes so far have been with structures that are flat and hollow.

A comparison with an established transplantation method

While bioprinting offers the potential of building complex tissue structures, there are some limitations on bioprinted tissues compared to traditional transplant methods such as xenotransplantation. As mentioned above, one significant disadvantage is the limitation on accurately replicating the architecture and function of the human organs, as well as the difficulty in having constant vascularization that’s essential for providing nutrients and oxygen to tissues. This could lead to premature tissue failure. In contrast, xenotransplantation involves transplanting animal tissues or organs into humans, which means the complexity and functionality of the biological structure is already established. However, this method raises huge ethical concerns in animal rights and the risks of cross species disease transmission, which could introduce new zoonotic diseases. Additionally, the human immune system recognizes animal cells as foreign, triggering immune responses that sometimes lead to immediate organ failure. The genetic differences between species make it challenging to match the immune system’s expectations. Over time, the transplanted organ may gradually lose its function after experiencing ongoing immune attacks. As a possible way around this, scientists are exploring genetic modifications in animals to make their organs more compatible with the human immune system, but this remains as a high risk procedure due to the unpredictable nature of immune responses. Bioprinted tissues also face rejection issues; the materials used in the bioprinting process, such as scaffolds, may trigger an immune response if they are not fully biocompatible with the recipient's body.

Conclusion

While researchers are busy incorporating ways to combine blood vessels into bioprinted tissue, there is a tremendous potential for bioprinting to solve critical healthcare challenges, to save lives and advance our understanding of how human’s organ function in the first place. Ongoing research continues to explore the possibility of bioprinting other fully functional organs, bringing us closer to revolutionary breakthroughs in regenerative medicine.

This bioprinting technology opens up a dizzying array of possibilities - have you ever thought about printing tissues with embedded electronics?! Could we one day engineer organs that exceed current human capabilities? - Giving ourselves features like unburnable skin? How long may we be able to extend human life by printing and replacing our organs? Who and what will have access to this technology with its incredible output potential?