Can Everybody Have Clean Water?

Contributions by Gregorio Secchi, Pasha Keray, James Brooks, and Richard Brooks

Access to clean water and proper sanitation is a fundamental human right, yet millions worldwide still struggle with water scarcity, pollution, and inadequate hygiene facilities. Currently, over two billion people are affected by the lack of safe water, and in 2024 alone, 3 million people died because of this. The United Nations' Sustainable Development Goal 6 (SDG 6) aims to ensure the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all by 2030.

Challenges in providing clean water

The primary drinking concerns regarding water are microbes, microplastics, and toxic chemicals. While microbes can be easily eliminated by heating the water, filtering out microplastics and toxic chemicals is far more complex. Already existing methods, such as desalination and reverse osmosis stations, are highly effective but extremely expensive. This article will explore an innovative solution that seeks to achieve the same purification results as these costly systems —at a much lower cost— through the use of hydroponics.

An Innovative Solution

Hydroponics is a soil-free method to grow plants which uses a solution of water which provides necessary minerals to the plants. Hydroponics is widely used in the agricultural sectors for growing ornamental crops, herbs, and various vegetables such as cucumbers, lettuce, and tomatoes. However, beyond farming, hydroponics could be exploited to produce safe drinking water. This can be done by collecting the product of transpiration, water. Transpiration is defined as the natural process where plants release water vapour from their stems and leaves. Through this method, it becomes possible to produce clean water free from toxic chemicals, microorganisms, and, most importantly, microplastics.

The Science of Hydroponics

Plants have specific dietary requirements, much like any living organism, needing nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium to sustain growth and metabolic functions. In hydroponic systems, these essential ‘meals’ are dissolved directly into the water, ensuring efficient uptake by the roots. The method which will be used in this solution, Deep Water Culture (DWC), not only delivers this nutrient-rich solution but also provides continuous oxygenation, keeping the roots well-fed and breathing—critical for healthy growth and cellular respiration.

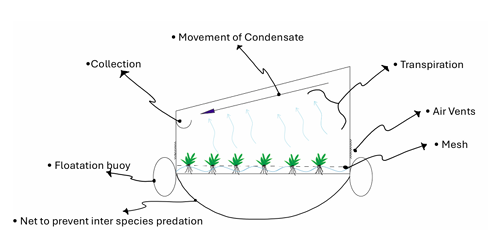

How the Farm Works

The farm's concept is straightforward: capture the water released by plants and store it in externally accessible tanks. As plants release water vapor, the farm promotes condensation by gradually cooling the environment through increased ventilation and manual cooling systems, such as pumps that circulate water to the roof. Additionally, the ventilation fans help direct the condensed moisture toward collection basins along the farm's perimeter, where it is then stored in tanks for easy access.

Can it Be Enough?

However, several questions must be addressed to make this solution viable. Firstly, how can we be certain that enough water will be produced? To answer this question, we must first consider the plant we choose. Sea purslane will be used due to its ability to thrive in brackish and saline waters as well as its high salt and drought tolerance, which ensures water production year-round. Under optimum conditions, one square meter of sea purslane will produce between 8 and 12 litres of water per day. Yet, these figures rely on optimum conditions, which begs the second question: how can optimum conditions be consistently achieved?

Optimising the Environment

Optimum conditions for transpiration are those that maximise a plant’s water release. For sea purslane, this would mean high sunlight exposure is required as well as temperatures between 25ºC and 30ºC, low humidity, an adequate water supply, and mild winds. One significant challenge is optimising the salinity of the water as sea purslane optimally grows in salt waters that are no more than 2% salt whereas the average salinity of the sea is 3.5%, significantly more saline than required. However, reaching the required salinity is expensive, thus a necessary choice must be made; the salinity of the water will not be changed in order to maintain the original aim of this solution, providing clean drinking water for a lower cost than existing solutions.

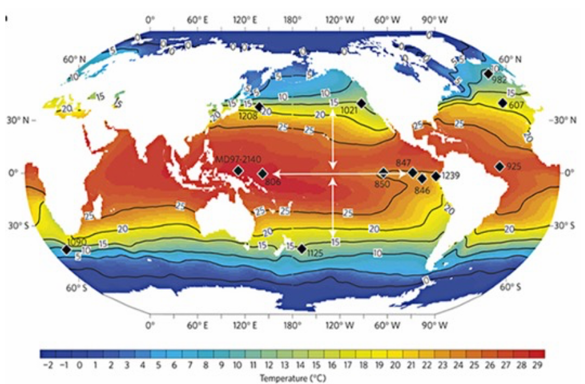

Another factor that is difficult to control is the humidity of the air. Since this system relies on transpiration, naturally humid conditions will be created due to the water being released. Because these two factors will not be controlled, the expected yield of this system goes from a maximum of 12 litres to around 7 litres of water per day. On the other hand, maintaining temperatures between 25ºC and 30ºC, high sunlight exposure and providing mild winds prove a much easier challenge. Both the issue of sunlight and temperatures can be easily solved by geographical placement. The farms must be built in countries that have coastal temperatures between 25ºC and 30ºC as well as sufficient sunlight (often, in areas with these temperatures there is sufficient sunlight). Countries such as Eritrea, Papua New Guinea and Somalia all fit this geographical requirement. As for the wind, air vents will be installed on the walls of the farms to provide the required ventilation. The air vents will be powered by their own solar panel to reduce electricity costs and to provide consistent electricity supplies. Because it is possible to have optimum temperatures, winds and sunlight, 7 litres of water per meter squared of sea purslane can be collected every day.

Cost-effectiveness and Sustainability

While we have successfully addressed how to obtain optimal conditions and demonstrated the potential for significant water yields, one final question remains: can this solution remain cost-effective whilst using sustainable materials? Before addressing this question, it is important to acknowledge that a higher investment in materials will produce better results. An inexpensive approach to building this farm would be to use plastic sheets and local timber. Both of these materials are incredibly easy to find, are inexpensive, and produce adequate results. However, the durability of these materials can be put into question as plastic sheets are easy to tear and wood (without proper treatment) can rot in these conditions. The more durable solution would be to use twin wall plastic and aluminium beams, both made from recycled materials. These options are more durable, which will reduce long-term maintenance fees. In both cases, clear plastic will be used to allow light exposure. A net will also have to be used to protect the plants from predators. Here, sustainability can be maintained by using nets made from recycled plastics or repurposing abandoned fishing nets—both eco-friendly options align with the original goal.

Target countries and farm implementation

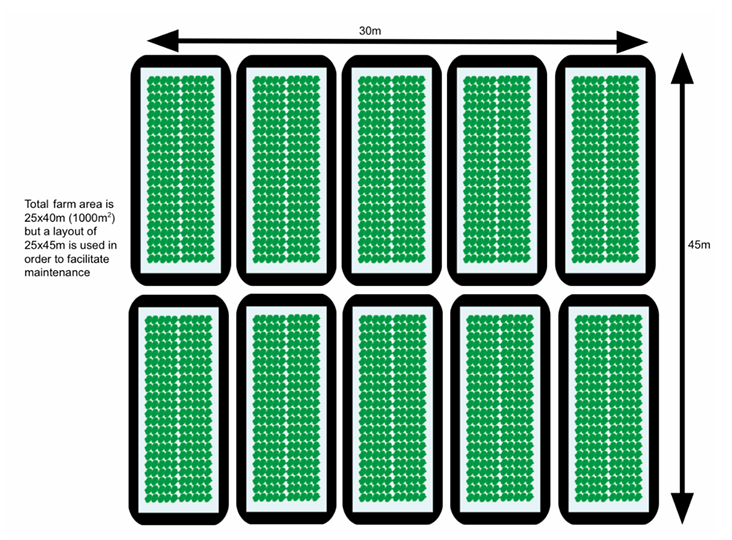

It goes without saying that this solution is inherently dependent on coastal areas, making it unviable for landlocked countries. This solution is primarily designed to target countries with lower GDPs that also struggle with supplying clean drinking water to their citizens. Countries such as Eritrea (where only 20% of the population has clean water access), Papua New Guinea (40% access), and Somalia (50% access) are prime candidates for this solution. To keep costs low and maximise community benefits, local labour should be employed in building and maintaining these farms. This not only reduces expenses but also creates much-needed job opportunities. The proposed farm dimensions would be 10x10m or 20x5m to provide enough space for efficient and easy maintenance while optimising the effectiveness of each farm. These farms would then be organised into one larger farm of far greater dimensions. 100m2 of the farm will be able to produce 700 litres of water per day when operating at its most efficient and around 400 litres on a bad day.

Conclusion: A sustainable, scalable solution for clean drinking water

For a quarter of the global population, access to clean drinking water remains a critical challenge. While industrial solutions like reverse osmosis are highly effective, their high costs and maintenance requirements make them unviable for many low-income regions.

The hydroponic-based approach offers a cost-effective, environmentally sustainable alternative by utilising sea purslane’s natural transpiration process. With optimal conditions, this system can produce approximately 7 litres of purified water per square meter daily. When implemented on a large scale, it has the potential to provide daily water to 3 million people per square kilometre of farm.

By leveraging local resources, sustainable materials, and renewable energy, this solution is not only practical but also fosters economic opportunities in the communities most affected by water scarcity. If adopted widely, it could play a transformative role in addressing global water insecurity—bringing us one step closer to achieving universal access to clean water.