Living together: trading genes, Allen keys and coexisting peacefully

While we think of parasites as freeloaders, who knew playing host to parasites could come with perks? From elephants and oxpeckers to worms and bacteria, nature is packed with symbiotic relationships where both parties gain from the relationship. These partnerships fall into three categories depending on who they benefit: mutualism, commensalism and parasitism. While the advantages are obvious, even parasitism can sometimes lead to a balance, with the emergence of a peaceful equilibrium.

Multicellular organisms rely on the division of labour by individual components to survive. The existence of symbiosis comes from the symbiont often providing a process that the host is unable to carry out themselves, and therefore is of value and benefits the host. In fact, symbiosis was key in the origin of life, where near deep sea hydrothermal vents, the lack of light for photosynthesis means organisms are dependent on alternate metabolic processes. Within the vents themselves, another source of energy is offered: large quantities of sulphur compounds. The bacteria present are chemosynthetic, meaning they can use these minerals in the water to release energy for self-sustenance. Vent mussels and tube worms rely on this symbiotic relationship, where they have evolved to have these bacteria residing internally in their gills and trophosome, and rely on the bacteria to produce a food source of organic molecules. Both the bacteria and the worms are the winners; bacteria are given a cozy home away from the extreme vent environment, and the worms are provided with essential nutrition.

What is so special about these symbiotic relationships is that the organisms are intertwined in their own development as well. Imagine your friend buys an Allen key for their bicycle, and all of a sudden you and the whole neighbourhood can use the one tool to improve all of your cycling abilities through adjusting your bike seats. In fact, for several organisms, this sharing of traits is a real possibility via horizontal gene transfer.

Organisms evolve together rather than separately, including developing new adaptations and even taking genes from each other. Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) is different to typical inheritance, as genetic material can be passed to another organism, bypassing being via the offspring. This can be via the uptake of free DNA present in the environment, via conjugation, the direct transfer of DNA between cells through physical connection, or via transduction, the transfer of DNA via viruses. Occurring mainly with microorganisms such as bacteria and retroviruses, it enables the rapid acquisition of new traits and increased biodiversity.

In the gut microbiome, HGT is necessary for the adaptability and diversity of gut bacteria, as the exchange allows the microbiome to respond to external changes in environment, including diet or new medicines. However, these HGT processes are crucial and disruptions to them can quickly lead to imbalances in the microbiome, associated with several health conditions including obesity, diabetes, autoimmune diseases and gastrointestinal disorders. HGT is powerful; its rapid ability to spread HGT has the capacity to quickly change health, but its rapid effect can also be harnessed positively for engineering bacteria that can restore a healthy microbiome.

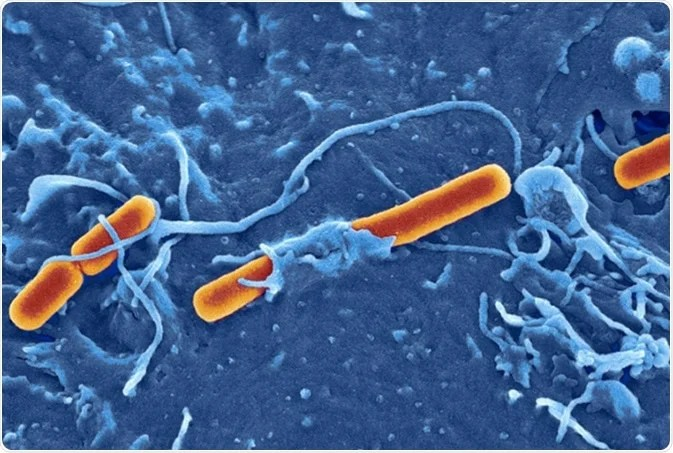

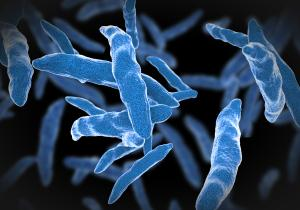

Symbiotic relationships are ever changing, but most strikingly, can evolve to an equilibrium where the parasite is no longer harmful to the host. This has been the case for several diseases. For mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), several strains of the Mtb have evolved to be less harmful to mammals, allowing for longer transmission periods. These strains are able to remain dormant in the human body for several years, and then can reactivate afterwards, meaning that as they are a chronic condition they are more successful in infecting new hosts. This host-pathogen evolution is beneficial to both the host and the symbiont as the Mtb is more likely to continue to be transmitted due to longer windows and the host is less severely affected due to the pathogen becoming less virulent and deadly. Even for parasitism, the evolution of the two organisms in symbiosis can be beneficial to the infected host.

We do not exist in isolation; rather, life revolves around our connections with other organisms. Neighbouring organisms and nearby friends can be helpful, even parasites. As we continue to evolve together, it is clear that thriving will depend on the company we keep.