Stroke after Stroke: How a Stroke Happens and How to Prevent a Secondary Stroke

‘Stroke’, a word describing a string of symptoms, is closely connected with another word ‘palsy’ (paralysis), deriving from an umbrella Greek term ‘apoplexia’ (apoplexy), meaning being struck by a deadly blow. It was used by Hippocrates to describe his patients’ experiences: sudden pain, unresponsiveness and urinating without awareness. Strokes are quite common among people above 65, with around 800,000 people experiencing strokes per year, it even earned the gold medal for the most common cause of adult disability. In this article, we will explore how a stroke occurs, why a secondary stroke happens and the best methods of preventing it.

The first stroke (the primary stroke)

Before we dive into secondary strokes, I would like to take a moment to explore how a stroke happens and the causes of it.

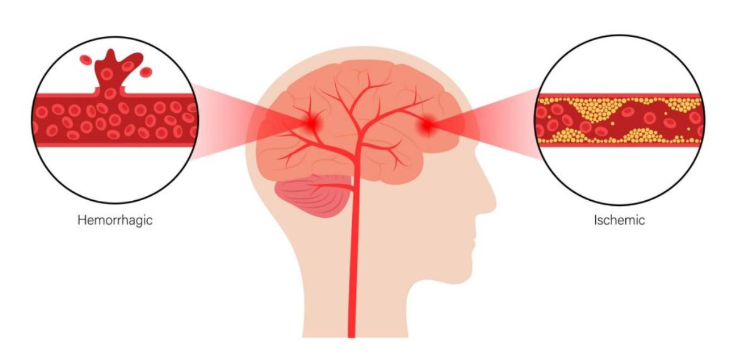

A stroke is caused by a cut off of blood from the heart to the brain. This could be caused by a blockage or bleeding.

There are 2 types of strokes: ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes.

Ischemic strokes occur in 2 ways: atherosclerosis resulting in endothelial cell dysfunction and embolism.

Atherosclerosis happens when plaques form in the inner layer of arteries (for biology students: the tunica intima), plaques normally form when the endothelial cells are damaged (for example, tobacco damaging the cells); the formed plaques do not cause strokes in most cases as they take years to build up and only blocks a section of the arteries, allowing a smaller volume of blood to pass through. A stroke is caused by a sudden blockage of the arteries, and here is how it happens: the constant blood blow towards the brain causes the outer hardened layer (the fibrous caps) of the plaques to get ripped off because of the friction, thus exposing the inner layer of the plaque. The inner layer of the plaque is thrombogenic, meaning blood clots easily there, resulting in many platelets blocking the artery; this process could happen in less than a minute.

Embolism happens when a blood clot travels along the artery and gets stuck later in a smaller lumen (an artery, arteriole or capillary). The blood clots could have originated from atherosclerosis or previously stagnant blood (this could have happened if a person had a heart attack).

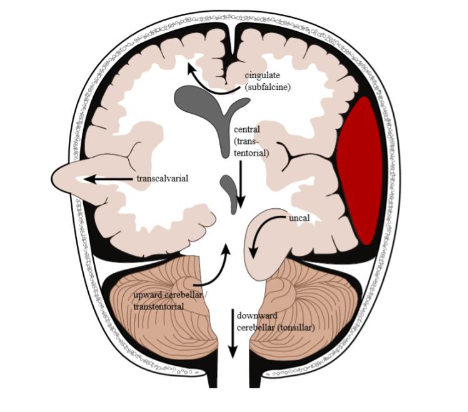

The blockages cause a certain area in the brain to lose oxygenated blood, causing ions such as Na+ and Ca2+ to build up. This causes damage to the organelles and the cell surface membrane in the cells and causes degradative enzymes to seep out of the cells. The immune system tries to fight back by causing inflammation in a specific area of the brain, damaging the blood-brain barrier. This causes larger molecules like proteins to get into the brain tissue, causing it to swell. This will then result in some brain tissue being pushed towards a side of the skull or even into the brain stem (herniations), causing the symptoms of a stroke.

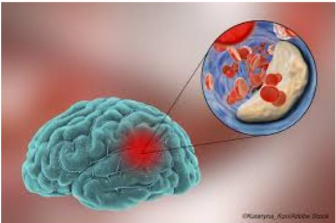

Hemorrhagic strokes are caused by ruptures in the arteries, typically in the cerebrum (the top large part of the brain), they are called intracerebral haemorrhages. The most common cause of a hemorrhagic stroke is hypertension (high blood pressure). The high pressure pushes proteins from the blood into the walls of the arteries (the tunica media), causing it to harden after a prolonged time, making it easier to rupture, this is referred to as hyaline atherosclerosis. Another way of causing haemorrhages is microaneurysms, which are small bulges in smaller arteries, normally supplying blood to the inner cerebrum.

When a haemorrhage occurs, the blood in the arteries spews into the brain tissue, causing pressure to be applied to nearby brain tissue, vessels or the skull and reducing oxygen to some areas of the brain. This can cause brain damage as less oxygenated blood is reaching specific areas, therefore potentially causing cell death as the cells cannot respire. Pressure can cause herniations, pushing the brain in different places. Depending on the location of the haemorrhage, different symptoms of a stroke can occur.

The Secondary stroke

Now that we know how a stroke arises, we can explore how a secondary one happens. For primary stroke survivors, there is around a 20% chance of that person experiencing another stroke, meaning that it is more likely for a person to get another stroke after the first one. This can occur within a few days after the first stroke and patients remain vulnerable for up to a year afterwards. The symptoms of a secondary stroke are more severe, and the mortality rate is much higher.

The cause of a secondary stroke is very non-specific. It comes from a multitude of factors, but in terms of mechanisms, they are generally the same as how a primary stroke occurs. Recent studies have shown that a secondary stroke is normally the same type as the first; for example, people who had an ischemic stroke would typically have an ischemic stroke as well for the secondary stroke, and vice versa. Cancer, heart defects and genetics all can contribute to the occurrence of a secondary stroke.

Stroke prevention

The best way to prevent a second stroke is to fix the patient’s lifestyle. Quitting smoking, being active, losing weight, controlling glucose levels and managing their diet lessen the chances of suffering from a secondary stroke.

Spotting a stroke early is also essential for a patient’s survival. The acronym FAST describes the common symptoms of a stroke and is useful for identifying whether a person is having a stroke.

Looking out for signs such as face drooping (whether their face has fallen on one side), arm weakness, and speech difficulty (slurring words) are important to identify a stroke. Time is not a symptom, but a reminder that the sooner a patient gets professional medical attention, the higher the chances of recovery. So, the next time you see any of these symptoms, remember to call for help as soon as possible.